Death is the second leading fear in the country, preceded only by public speaking. (Guess it’s true that people would rather die than give that presentation in their next business meeting.) So, what kind of person is so comfortable, even passionate about death that she would make it her career and life’s mission? Am I some sort of Goth wierdo, sitting around in the dark lit only by atmospheric candles and burning incense, surrounded by skulls and taxidermied mutants and listening to Mozart’s Requiem 24/7? Not at all. I’m an outgoing, gregarious person that prefers a traditional conservative decor and laughs at pictures of cats just like most of you. (Although, I will transform my surroundings for Halloween, I do not live like this the rest of the year.)

It is true I enjoyed The Cure and Bauhaus and The Smiths as much, well probably more, than the typical Gen-Xer in the 80s. I wore a lot of black, preferred dark comedies like Heathers and old noirs to rom-coms and other popular culture. I read everything by Edgar Alan Poe and Stephen King I could get my hands on. I became a fan of horror films and Twilight Zone-style anthology television and Alfred Hitchcock. All of this not because I was depressed and obsessed with death or death culture, but because I was an American teen coming to age during the Cold War and the rise of the AIDS epidemic. Death was all around us, but Reagan gave us “star wars” (not the good ones, mind you.) and as long as we were “good,” – no sex or fooling around, or you’d be the first to die at the hands of the slasher d’jour – it never really came to our doorstep.

My dad’s youngest brother was electrocuted in the bathtub when he was only 16, but I was 6 and didn’t really have a relationship with him and did not have many memories of him, although I know my childhood relationship with my grandparents, especially my grandmother, was colored by the ever present grief surrounding us. But I did not have a lot of childhood deaths, otherwise.

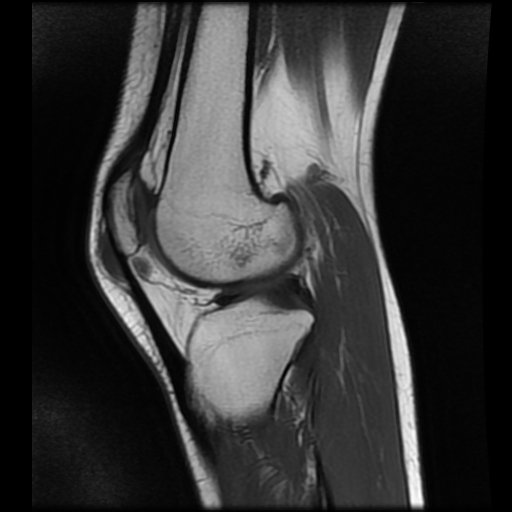

Then at 19 I was diagnosed with synovial cell sarcoma. An orthopedic surgeon removed a softball-sized tumor from my right knee right after Thanksgiving in 1989. Because I had been bothered with knee pain and sensitivity since at least 1983 or so, none of us were concerned until the biopsy came back as a very rare, very aggressive, malignant cancer. We hurriedly made plans to see an orthopedic oncologist, and although worried to hear the “C” word, I don’t think I realized the extent of the danger of the diagnosis until I entered his office a couple of weeks later. In the times before WebMD and the Internet, I was not inundated with images or stories of people who had the same diagnosis, and I certainly didn’t know anyone who had this diagnosis. Reality was in that waiting room filled with patients, many of whom who were missing limbs, lower legs and arms, complete arms or legs. The serious conversation with the surgeon about what exactly it was, and the possible outcomes revealed this was a big deal. This could kill me. I could die. (Below: case courtesy of Dr Ammar Haouimi, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 67366)

Death had arrived at our doorstep, bags in hand, ready to settle in and become a constant, quiet roommate and companion. It lurked in the backs of our minds. It lurked at our dinner table. It lurked in the quiet of our separate bedrooms each night before bed as my parents held whispered conversations and weeping prayers for healing and safety. In my room, I, too, had some whispered conversations with death for a time; subjecting it to all the phases of this anticipatory grief: anger, denial, depression and bargaining and finally, acceptance. I arrived at the acceptance phase of my diagnosis relatively quickly. An internal faith or perseverance led me to believe that people died every single minute of every single day, and many of them from things like cancer that came from nowhere for no reason. I certainly was not some special exception to the rule that death comes for us all. If it was my time, I would die. I certainly added nothing to the quality of my days or my time worrying about it.

Since I am writing this blog post 30 years later, it goes without saying that I was extremely lucky. Death, while making its presence known, did not come for me that day, those weeks, months, or years later. Surgery, radiation and nearly a decade of follow-up scans and tests proved that I had avoided its grasp for the time. But death never left my consciousness from that day forward. I’d love to say that I walked bravely into those post-cancer days with a newfound love for life and set the world on fire with my knowledge and passion of the fleeting nature of life. Truth is I floundered for many years. In truth, my attention turned to finding employment that would give me health benefits that would help cover the cost of yearly bone scans, cat scans, MRIs and X-rays. Truth is I had a chip on my shoulder that I lost the rest of my relatively carefree collegiate years to worries about dark images on those scans and the financial fears of paying for them. Truth is (and I really only discovered this about myself since re-addressing my relationship with death) I got married too early to the wrong person from fear I would never meet the right one in time. The truth is none of us ever talked about Death even though it was a usurper of our daily lives: not my family, not my friends, not the doctors. Death stood breathing on our necks, and we ignored it.

In the following decade, Death came out of hiding more and more frequently. My great grandfather, great grandmother and paternal grandfather all died before I was 25. A friend’s mother died from breast cancer. I mourned for all of them. A childhood friend died at 28 in a Marine helicopter training accident. I returned to my childhood hometown for his funeral and cried from the moment we crossed the city line and didn’t stop the entire time I was there. I eventually remarried, and the past decade since have experienced numerous deaths on my husband’s side of the family.

Death had come back out in the light of day.

Then my mother was diagnosed with a glioblastoma. Unlike the breast cancer she had twice, this was a cancer for which there would be no cure. She was lucky that her tumor was operable, and she came out of brain surgery with flying colors. She pursued radiation and oral chemotherapy. She played around with wearing some electrodes on her head, but she never fully committed to that treatment, and it came back with a vengeance. Nine months after being diagnosed, she died, at home with me, my brother, and my dad by her bedside. It was sad, but moving, and I felt so weirdly grateful. Grateful that she – her heart, soul, essence, whatever you want to call it – had been able to escape that mortal shell that had failed and pained her so many times.

She had been too scared of Death to talk about how her body was failing her. We didn’t know how much difficulty she was having getting her diseased brain to communicate with her motor functions. She did not tell us how much her head hurt or how fatigued she was from her treatment. She was afraid of Death. Looking back, I regret that I did not force Death, the elephant, into the light and talk to her about the inevitability that faces us all, but especially her, the woman with a glioblastoma coming back with a vengeance around the surgical cavity left in her brain . She was “losing her battle.” And I know now that she wouldn’t talk to us about Death, because her being unable to “win” some sort of unfair and unjust war made her ashamed and made her feel like a loser. She told me she was lazy, when fatigue and pain kept her in bed or in her recliner all day. Lazy. The woman dying of a brain tumor thought she was being lazy, and if she could just muster a little energy, she could “beat” this thing and go to Virginia Beach to visit family.

Death was not her enemy. Death is no one’s enemy. Death is the back of the coin fronting life. Death and life are yin and yang – partners in an eternal tango. Mom could no more defeat Death than a twig could defeat a tornado. And I was depressed and sad, not because my mother died, but because my mother died thinking she had died due to some sort of personal failing. And that pissed me off.

I am not angry at death. My passion does not come from some mistaken belief that I can stop death. I cannot nor do I want to. I am angry at a society, a healthcare system, a religious system that indoctrinates us to believe that death is the ultimate enemy and that we can gird ourselves as soldiers with enough thoughts and prayers and treatments, no matter how poisonous and futile, against it and somehow win. I’m angry at the casual way we throw around the phrases like “fighting” cancer or disease, “beating” cancer or disease. Because my mother “fought” breast cancer twice and “won” and had convinced herself she could beat a brain tumor that has a zero survivability rate. She saw her inability to overcome death from a glioblastoma as a failing of her faith and will and herself.

I acknowledge Death in the room, now. I turn the light on and let it come out and dwell in life and contribute to my plans and decisions. I talk about Death with friends, family and, now clients. I want everyone to know that Death is not an enemy. Death is the last step in a journey in this place and on this plane. Death is only the end of the body in which we dwell, not the end of “us.” Death cannot be defeated. Death cannot be skipped or cheated or outrun or out smarted, so we cannot define ourselves as failures for our inability to do so.

Thank you. I often wondered how Janet felt. Now I know she was just normal and scared. This can show me there is a light in our dark place. As I see my mom grow closer to that final stage of life.

LikeLike

The strange part, of course, is that people who shared their dying with me (many times they were cancer patients) also shared with me what it means to live.

LikeLike

Absolutely. Knowing you will one day die helps us define life. It’s the most common lesson imparted from those facing the end of life: live every day like you’re dying and take nothing for granted.

LikeLike

Great writing. Your mom would be so proud of you for what you are doing. I wouldn’t say I am afraid of death at all, but I do want to hang around as long as I am able to contribute in some way. Yet, I am not doing everything I can to live as long as possible, so there’s that. Lots to unpack on this subject, I’d love to learn more, I’ve never heard of your type of service until (your cousin-in-law?) AH told me about you.

LikeLike